The Bank of England’s governor said a decision to cut interest rates is “an important moment in time” but warned people not to expect a sharp fall in the coming months.

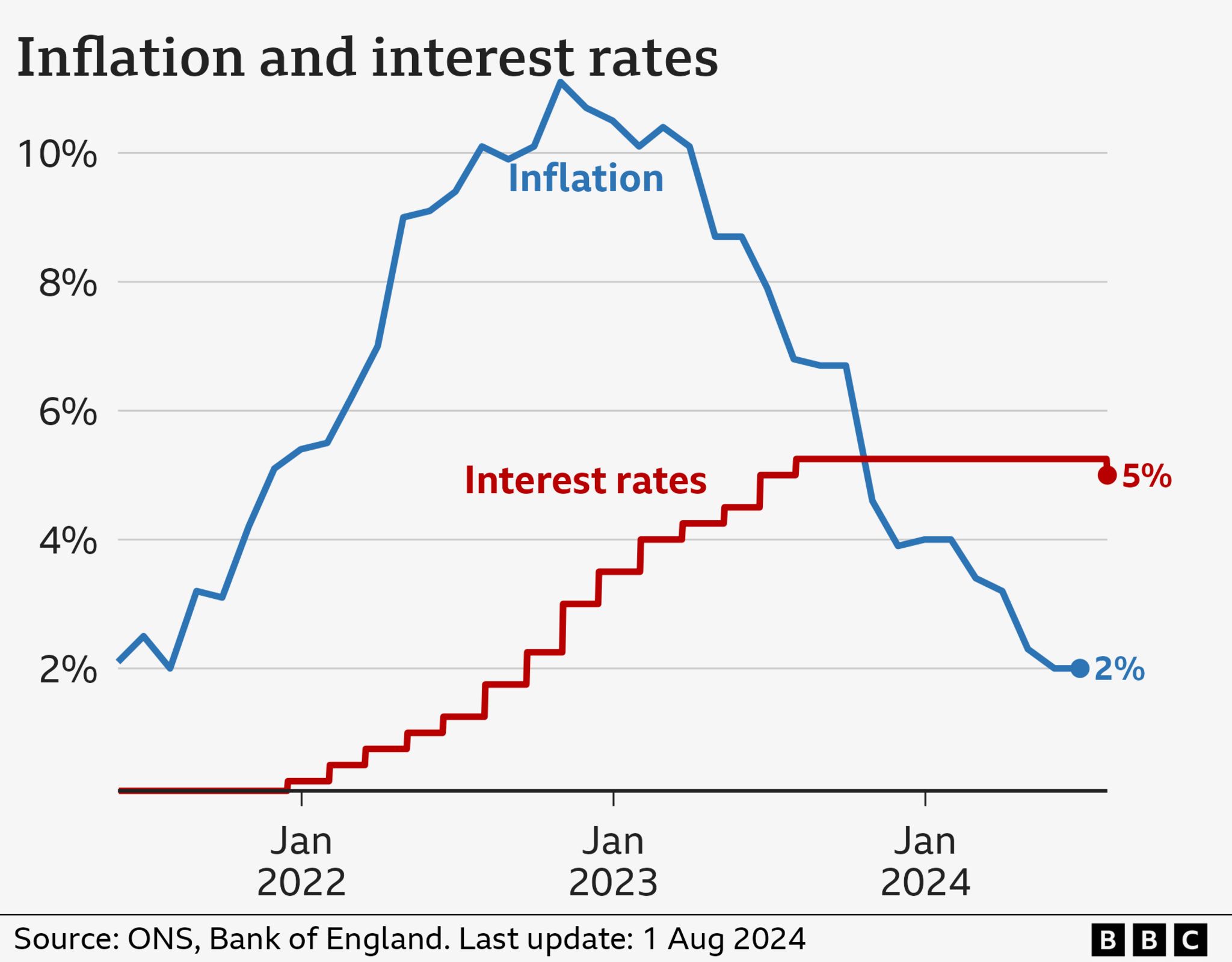

In a closely-run decision, rates were lowered to 5% from 5.25% on Thursday, marking the first cut since the start of the pandemic in March 2020.

Interest rates dictate the cost of borrowing set by High Street banks and money lenders for the likes of mortgages and credit cards.

Bank governor Andrew Bailey said that lower inflation had paved the way for the fall in interest rates but told the BBC it was “not mission accomplished yet”.

He said policymakers needed “to make sure inflation stays low and be careful not to cut interest rates too quickly or by too much”.

Interest rates have climbed over the last few years, as the Bank has battled to control soaring price rises.

The higher rates have put pressure on household finances, although returns for savers have improved.

The fall to 5% means that homeowners on tracker mortgages will see an immediate reduction in their monthly mortgage payments. Those on variable rate deals may also benefit from the fall.

But many homeowners on fixed rate mortgages still face the prospect of much higher mortgage rates when those deals expire over the next few years.

‘People are restricted with what they spend’

There are hopes that falling interest rates will improve consumer confidence, which has been subdued.

Rupali Wagh, co-owner of Tukka Tuk street food in The Cardiff Market, said the interest rate cut has made her feel “hopeful” as it will eventually lower the payments on her business loans and means some customers will have more disposable income.

While trade has picked up recently because of the hotter weather, some customers were still ordering less and trying fewer things from the menu.

“They’re very restricted with what they spend. I have never had so many conversations on the table about mortgages and expenses,” she said.

You can read more from people the BBC spoke to about the potential impact on their finances here.

‘One and done?’

Mr Bailey was asked by reporters if the interest rate cut was “one and done” – that is, will there be no more cuts after this?

He said that he has no view on the path of rates and that the Bank would decide from meeting to meeting.

Although on Thursday, financial markets predicted that there was a 75% chance the Bank would cut rates again in November, after the Labour government holds its first Budget at the end of October.

The decision by the Bank’s nine-member committee was finely balanced – five, including Mr Bailey, voted for a quarter point cut.

The Bank’s chief economist Huw Pill was in the minority of four who voted to hold interest rates.

He later told a virtual Q&A that monetary policy – the action a central bank can take to influence how much it costs to borrow or save – should not “take its eye off the ball” when it comes to the cost of living.

“There are other instruments… that can be much more finely tuned and are much more surgically targeted to help people in need at the bottom,” he said.

“And using monetary policy [in that way] may detract it from what it can actually do.”

He suggested monetary policy’s job is to help the less well off by keeping inflation at 2%.

While the interest rate cut will be a boost for some homeowners who have been squeezed, the Bank of England signalled that a mortgage shock still lay ahead for others.

Around a third of people with a fixed-rate mortgage are still paying less than 3%, after getting a deal when interest rates were a great deal lower.

The Bank said that most of these home loans will expire before the end of 2026 “meaning that effective interest rates will rise somewhat further over that period”.

The inflation rate – which measures the pace of price rises for goods and services – hit the Bank’s 2% target in May and has remained there.

But core inflation, which strips out volatile elements such as food and fuel prices, remains relatively high. And the Bank expects inflation to rise in the second half of this year as energy bills tick higher in the colder months.

The Bank noted that wage growth – which can worsen inflation – had slowed but would continue to monitor it.

It does not, however, expect a recent public sector pay rise promised by Chancellor Rachel Reeves to have a major impact on inflation.

Ms Reeves confirmed offers of wage increases of between 5% and 6% for public sector staff including NHS workers and teachers on Monday.

Based on “back of the envelope” calculations, Mr Bailey suggested they would have a “very small” effect.

Ms Reeves welcomed the rate cut but said that “millions of families” still faced higher mortgage rates because of former Prime Minister Liz Truss’s mini-budget.

She added that the government was “taking the difficult decisions” to fix the economy after “years of low growth”.

But Conservative former prime minister Rishi Sunak claimed on X that Labour’s “inflation-busting public sector pay rises” would put further interest rate cuts at risk, external.

On Monday, Ms Reeves claimed the Conservative government had left a £22bn “black hole” in public finances and had not been upfront about this.

The Conservatives have rejected this, claiming Labour is laying the groundwork for tax rises, which Ms Reeves has alluded to in an interview on the News Agents podcast.

The Bank confirmed that it had been briefed by the Treasury about the figures on Monday before Ms Reeves made her statement in the House of Commons.

Source: BBC (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cx72dpxy25do)